|

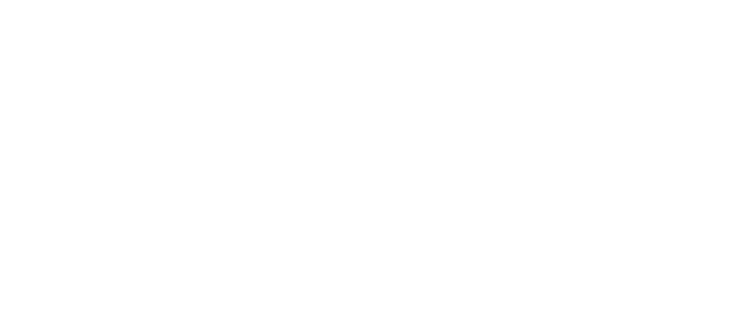

The Florida tree snail (Genus Liguus) range once extended from Pompano Beach to Key West and across the Everglades to Marco Island. It is hard to imagine a time when tropical forest trees were covered by their glistening shells. A tree snail was like an exquisite jewel.

Charles Torrey Simpson wrote, " Long before I began to collect (1882) man had wrought great destruction to the hammocks in which they live... they are on the verge of extinction. Great forrest areas have been cut.” Construction of the canals in Fort Lauderdale began in 1920 by clearing the mangroves and creating the first “finger islands” that became the trademark of Fort Lauderdale, “The Venice of America.” It was a model repeated by developers along the coasts, who were in the business of “selling mangroves” as they dredged and filled the wet lands and leveled the hardwood hammocks. On December 6th, 1947, the government set aside 1.5 million acres of protected land as Everglades National Park (ENP), one place where the bulldozers could not come. Federally designated threatened Stock Island tree snails were moved to N. Key Largo Hammocks as a part of mitigation for developers. Post WWII, a new generation of homeowners were on their way to South Florida. Common were sales pitches, like this one in 1952, describing the proposed development of Key Largo Beach: “Slumbering, awaiting the advent of fresh water and the mechanical work of modern machinery to restore this natural setting for the comfort and enjoyment of man today, this great flat rock key, high above the sea, on which great trees have survived for centuries, and thick with vegetation, lies basking in the sun with its frost free climate but tempered by the ocean breezes is this potential paradise.” Originally, every tree island, every plot of land had a different variety of liguus tree snail, with different bands and color variations based on their diet and conditions in their particular hammock. Conservationists were particularly worried about snails in the Keys, where U.S. 1 gave collectors easy access to the hammocks that were home to the snails. Collectors proposed that they transplant threatened snails to suitable hammocks in ENP. From the 1950's thru the mid 1960's, some 52 color varieties were relocated to 224 hammocks within the park.

“You build it and they will come,” an adage true, more now than ever before. Not long ago in Key Largo, there were still pockets of forest, and undeveloped waterfront; little by little all are being developed. There are regulatory things that have to be done when developers want to develop areas. Especially concerning the federally designated threatened Stock Island tree snails in the area. Mitigation goes on where park rangers have to go out and remove the snails, then the developers have to pay money and the question is what to do with the tree snails? They get put in suitable conservation lands in the refuges in N. Key Largo. This usually happened without a lot of people’s knowledge.

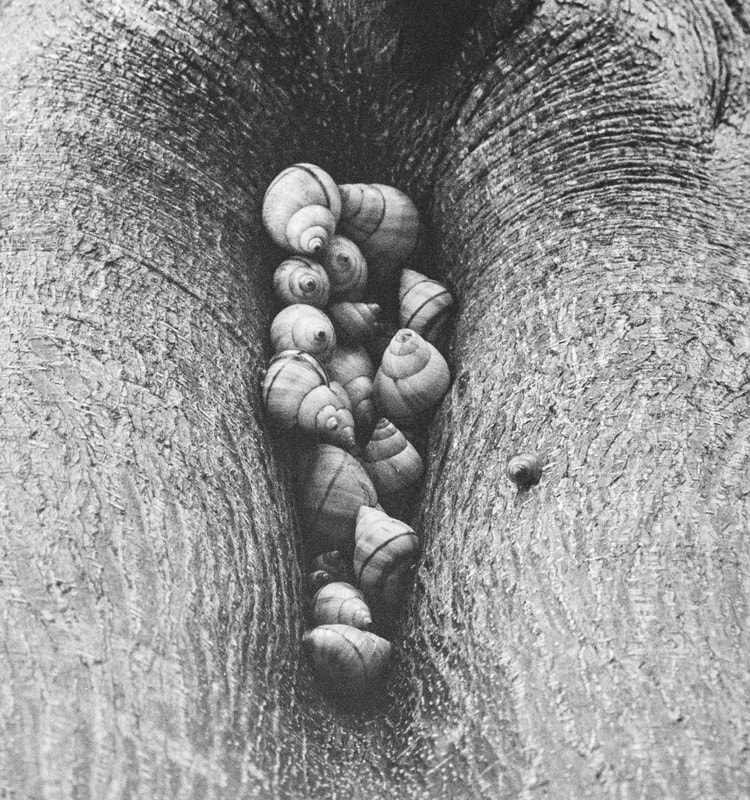

At the time, I did not understand the significance of what I was photographing. The accepted notion of moving and collecting has made science pause. Does conservation mean we must allocate a species to an area they were not native to, to forsake the environment of their origin? Our nature is a consequence of man’s actions. It would have been more interesting to know the Keys before people did what they did. Key Largo Beach city fathers predicted in 1969 the town would grow to 5000 by 1974

and 100,000 by 1990. Side-by side maps showing proposed development, and today’s current designation of the area as botanical and wildlife refuges.

0 Comments

The orchid is exotic, symbolic and fragile; it’s sheer existence is subject to the forces of nature. In an utopian world, where male and female parts coexist as one, close-up shapes containing near human forms, spur the imagination. Sharing this beauty with the world, enforces our role as co-occupants of a fragile and diverse planet.

“WHETHER YOU SUCCEED OR NOT IS IRRELEVANT, THERE IS NO SUCH THING. MAKING YOUR UNKNOWN KNOWN IS THE IMPORTANT THING.” – GEORGIA O’KEEFE Following her portfolio review, Sally asked, “What’s my next step?” I suggested it may be the next step outside her door. Comparing the scientist working on a cure, to an artist, it is the unknown which keeps us coming back.

Regular, spontaneous, and mindful time spent with a camera, are some key ingredients for satisfying new work. To achieve REGULAR: Capture vignettes with your iPhone on your daily walk. To achieve SPONTANEOUS: Be aware of atmospheric conditions that favor a good outcome. Diffused light on a calm day works for me every time. To achieve MINDFUL: It’s harder than it seems, but just be in the moment. Photographer and mentor George DeWolfe had me combine all three. His challenge: Photograph at the same location, every day, for 90 days. Conditions differed based on time of day, weather and my level of mindfulness. It was a hot, humid, buggy summer, in the Florida Keys native hardwood hammocks. Over time, the forest I chose, revealed much about myself. Let’s just call it an unfinished work. As George often reminded: “The difference between a good photograph and a great photograph is a tripod.” A serious photographer treats imagery via iPhone, rather like note-taking. If the subject is of interest, they return, at least once, with professional gear. My newest photographs on paper, aluminum and canvas are on display January 29th - February 8th at Ocean Reef Club Art League. New Works exhibit is open for preview and voting on January 28th. Georgia O’Keefe was best known for her paintings of large, zoomed in flowers. She created many different types of abstract art, but was admired especially as an independent female role model. The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum opened in Santa Fe following her death. |

CAROL ELLIS

This photographic website provides me the opportunity for self-expression, for sharing Archives

May 2024

TAGS

All

|

© Copyright 2022. Carol Ellis Photography.

All Rights Reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed