|

Often when people move to the Keys, the first thing they try to do is make their new home just like the place they left. Locals can pick up pretty quickly who these “they do it where I come from” newcomers are; within five minutes of meeting Angela and Brian, and observing their efforts to caretake our fragile Florida Keys environment, I knew they were a good fit here. They came down as a family when their middle child Logan was transferred to Coast Guard Station Islamorada, and once here, decided not to leave. Jokingly Brian and Angela aways said, “when the kids are gone we are going to quit our jobs, run away to the Keys and become bartenders, live in a one room shack with an A/C that is halfway broken and they wouldn’t care if there are roaches!” A positive twist on the old story “Come on vacation… leave on probation.” They researched house prices, and soon realized they couldn’t quit their jobs and become bartenders. Luckily, their jobs allowed them to work from anywhere, so they got more of their full dream than most anyone would want. The house they found online, located in Harry Harris Park, from an aerial view on Zillow, was your typical pea rock yard and stilt house property. The backyard borders a natural mangrove and buttonwood preserve, which if you were to crawl a few hundred yards through the County owned property, you could reach the shoreline. Soon after moving in Angela noticed shells near the A/C condensate drainpipe, picked one up, and saw it was a land hermit crab (Coenobita clypeatus). In honor of their new-found friends, Brian and Angela named their property ~ “Crustacean Plantation”. Never having had a hermit crab as a pet, her first reaction was “I don’t know how this works,” but she learned. She started by counting her hermit crab encounters, and began numbering the shells. At some point past 100 crabs she stopped counting. Hermit crabs have soft abdomens which require protection of a shell, and who require bigger shells to suit their bodies as they grow. She observed encounters where one crab was trying to hijack another crab’s shell. A crab will approach a shell, be it occupied or not and tap on it with it’s own shell. If it is occupied it will continue it’s incessant thumping until the resident crab gives up the shell willingly, or is evicted by force. Lost pinchers or legs found on the ground, are evidence of crab shell fights. Realizing a need, Angela started purchasing shells to put out in a designated “Transfer Station” and almost immediately small or broken shells were traded off for the new and roomier models, kinda like a used car lot for hermit crabs. Broken shells are left vacant, as they no longer provide protection or cannot hold fresh water needed to lubricate the crab’s gills. Angela and Brian have spent hours in the garden, adding mulch and soil, making new beds for the native and flowering plants, and adding water sources for the critters. Bricks and boulders line the raised beds full of soil and mulch. Hermit crabs need soil or sand substrate in order for them to molt; since the Keys doesn’t have dirt, the hermit crabs must surface molt or find leaves, and bury themselves during this vulnerable time. In their new beds, Angela and Brian have seen little dig piles where a hermit crab has gone to molt. We have provided them a “crabitat” - something they probably wouldn’t normally have. Creeping zoysia grass covers the former barren pea rock yard, leading up to an undisturbed tidal rocky area in the back of the property where the crabs hang out. As we approach we can hear clacking as the crabs retreat and their claw clamps shut the shell opening; hermit crabs have keen eyesight so it is hard to sneak up on one. We stare at the rocks, and soon detect movement; a shell blending in perfectly contains a hermit crab on the move. A sign “Hermit Highway” designates where the crabs cross to go to the ocean to lay their eggs, and after having done so return to the dry land to resume their lives. The “Crustacean Plantation” is on the Garden Club of the Upper Keys garden walk, Sat. Feb 17, 2024. It is located in the Harry Harris Park area, a hidden gem, full of natural beauty, and a livable community for those who work here, and the creatures who were here before we came.

You might want to bring along a shell or two for a hermit crab in need

2 Comments

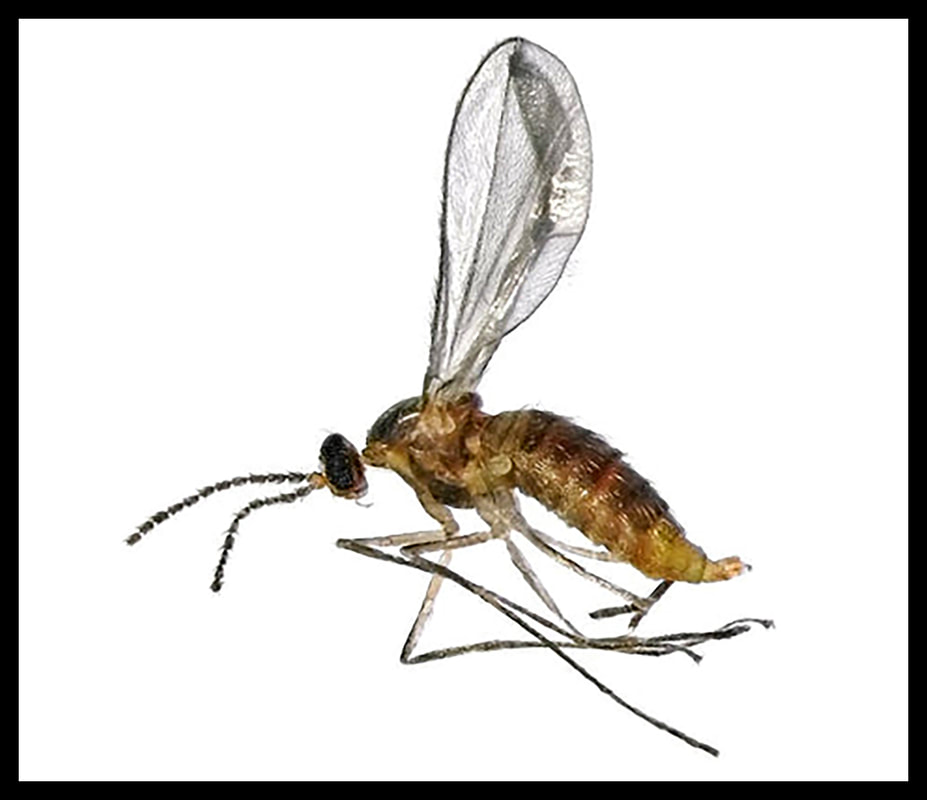

Imagine living in South Florida or the Florida Keys without some type of protection from the “mosquito”. Mosquitos are the most well known of the biting flies, but “no-see-ums,” their “all teeth”, nearly invisible cousin, are a force to be reckoned with. Belonging to the Ceratopogonidae family, their common name actually refers to a specific type of tiny biting fly. also known as midges, biting gnats, or sand flies, who depend on a supply of fresh human blood to reproduce, There are about four thousand species of these insects, found in almost all parts of the world, where there is suitable wet habitat for multiplying. The prevailing thought in the early 1900’s was that diking and draining the Everglades was needed to make South Florida habitable. Snowbirds came in December, and fled north in late spring, before it became muggy and buggy. Politicians needed more money, so their goal was to get people to visit longer, and eventually move here. Governor Napoleon Broward (1905-09), campaigned on a promise that “All that was needed to turn a worthless swamp into rich farmland was to knock a hole in the wall of coral and let a body of water obey natural law and seek the level of the sea.” Well, we know how that turned out. Florida's natural beauty laid waste to the bulldozer, and the natural drainage and filtering system, would be gone forever. I often wonder how the early settlers survived. The book “Charlotte’s Story”, tells the story of Russ and Charlotte Neidhauk who served as caretakers on the island of Elliott Key, the largest Key in Biscayne Bay, from 1934-35. They describe daily life without running water or power, farming and fishing to feed themselves. They lived in harmony with nature, using only what was available on the island or washed ashore via the “Overseas Lumber Company.“ Neidhauk wrote about mosquitos and no-see-ums: “When you get rain, you will soon have mosquitos. To get rid of mosquitos you need to eliminate the water where they live and reproduce. On the other hand sand fleas, live in just smelly, muck anywhere that has a food source and is damp. No way to eliminate them. To protect ourselves from them in the house, we oiled the screens, burned pyrethrum powder in a burner Russ had made with a pumice base and slotted coconut shell top. When we had to go out in them, we applied Vicks Salve to exposed areas. Eventually we discovered a screen paint which kept most of them outside. Mothballs dissolved in kerosene, helped keep these "Flying teeth" out. “ Ironically, Charlotte’s father, J. P. Arpin, had been a reclamation and drainage engineer for Gov. Broward. You just can’t control mother nature, The island was vacated after the Great Labor Day Hurricane of 1935, when salt water and waves submerged the island, destroying the homes and ruining the farmland. Island homes belonging to the early settlers, Conchs and fishermen, were close to the water, on dry elevated lots. They relied on prevailing winds to keep them cool and relatively bug-free. The "window" openings had screens and shutters, but no windows. My first apartment in the Keys was a “fish camp” type structure made from wooden forms, once used to construct homes in 1960’s era Miami. The landlord “Blinky” handed me a spray can of “Screen Pruf”, and explained this is what to spray on the window screens to keep the no-see-ums out. It was a thick black tar-like substance, and it definitely worked keeping out the bugs, but it sure messed up the view! These were the days before no-see-ums screen, a smaller 20 mesh size screen, which keeps no-see-ums out, though it does limit air flow through the screens. What can we do to live with no-see-ums? Spraying is not practical, as a new crop of no-see-ums are hatching daily. Environmental protections prohibit spraying pesticide over protected marshlands and water. We can wear protective clothing, or apply repellent. Bug repellents containing DEET are labeled for use against no-see-ums and mosquitos. A healthy alternative to chemicals is a homemade no-see-ums spray containing rosemary and alcohol. If you do get bit, wintergreen alcohol stops the itching within a minute and stays gone for hours. Best defense… It is a good idea to research vacation destinations and potential homesites, so you can avoid times or locations with critters present to “bug” you. Or take a lesson from your teenager… just stay inside in the AC tethered to your electronic device. The Keys are a sub-tropical mecca, for those seeking a life that is easy and breezy. At least that is the Tourist Development Council vision. In reality, competition for increasingly scarce resources, including housing, is a reality in the Keys… for humans and for the critters that live amongst us. It’s a dog-eat dog world out there, and you better not be wearing milk bone shorts. Not long ago the Green anoles were the majority of lizards found in my yard. Some had tails, and others not, thanks to my cats, but they were plentiful. They were great with camouflage, it’s body green when perched on a leaf, or turning brown when resting on a tree trunk. They did their job taking care of bugs in the yard, and provided a good source of entertainment. But then came the Cuban brown anole, a slightly larger lizard, easily identified by the mating male’s conspicuous bright orange dew-lap, and push-up behavior. They eat bugs and spiders… and other lizards. These Cuban cousins have more offspring than the Green anole; outcompeted and displaced, our native Green anole had to retreat to high in the tree canopy. Head for the hills, my Green anole buddy! See you on the ground someday. While cruising the islands of the Bahamas, I was introduced to lizards that had curly tails. I’d lived my entire life in Florida, but the Bahamas were the only place I’d seen these curious creatures. As it turns out, the Northern curly-tailed lizard was brought to Florida both as pets, and in the 1940’s sugar cane growers released them in their fields to control the insect population. These lizards can reach 11 inches, though most are around 7 inches in total length; they eat bugs and flowers, especially railroad vine, but also other lizards, particularly Cuban brown anoles. Hold your position in the trees, my Green anole buddy! I’ve got your six. Another lizard, the Peter’s Rock agama, began showing up in my yard around the end of 2020. Though first introduced by the pet trade in 1976, this lizard’s population really took off in the Keys, coincidentally during the pandemic, when the Keys were also “discovered” by an influx of new human residents, whose demand for second homes sent prices up, and the local workforce out. During mating season, Peter’s Rock agamas are pretty boys with boldly colored red heads, a black body, with more orange and ending with a black tip. Shy, they quickly retreat from humans, seeking cover under rocks or into the foliage. Both the agama and the curly-tail are sit-and-wait predators, who watch for crawling insects and butterflies. It’s no coincidence their favorite hangout in my yard is a coral rock covered by Corky-stemmed passion flower, the larval host plant for a variety of butterflies, including Gulf Fritillary, Julia Heliconian and Zebra Heliconian butterflies. The Peter’s Rock agama also preys on the Cuban brown anole. Whisky Tango Foxtrot! Take cover, my Green anole buddy. There is a large predator heading your way. It’s an invasion! The Green iguana was introduced to Florida via the pet trade; somehow they got loose and now are found in the Keys, to as far north as Tampa Bay, and all parts in-between. They feed on foliage, flowers and fruit, and will eat insects, lizards, small animals, nesting birds and eggs. The males grow to six foot long including the tail, that can whip you and transmit salmonella; alligators, dogs and raccoons are their only natural predators. They dig nesting burrows that contain an average of 40 eggs. These destructive burrows cause erosion and undermine seawalls, and can cause you to twist an ankle while walking near one. It is hard to calculate how many iguanas there are. A friend hunkered down in his home during hurricane Irma was amazed at how many iguanas were in the trees; as the storm raged on, soon revealed were dozens of iguanas, clinging to the defoliated branches. Cold blooded, they fall from the trees when temperatures go below 45 degrees, an opportune time to reduce their population. Green iguanas are here through no fault of their own, but I’m all for the death penalty due to their destructive behavior; call a Nuisance and Wildlife Management Pro, to do it humanely.  Adult iguanas feed on foliage, flowers and fruit. This male enjoying basking in the sun high above the reach of potential enemies. Adult iguanas feed on foliage, flowers and fruit. This male enjoying basking in the sun high above the reach of potential enemies. There is one reptile in my yard, who can be heard during May at dawn and at dusk, but rarely seen. It’s diet includes insects, baby birds, and small mammals such as nesting mice. It lives in tree crevices, and even inside structures, behind suspended ceilings or within walls. A native of Southeast Asia, the Tokay gecko’s call is described as “tuck-too”, too-kay; it was this sound that prompted U.S. troops in Vietnam to informally dub it the "F*ck You Lizard…” an informal “reception committee,” and the only ones there telling you the truth. |

CAROL ELLIS

This photographic website provides me the opportunity for self-expression, for sharing Archives

May 2024

TAGS

All

|

© Copyright 2022. Carol Ellis Photography.

All Rights Reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed