|

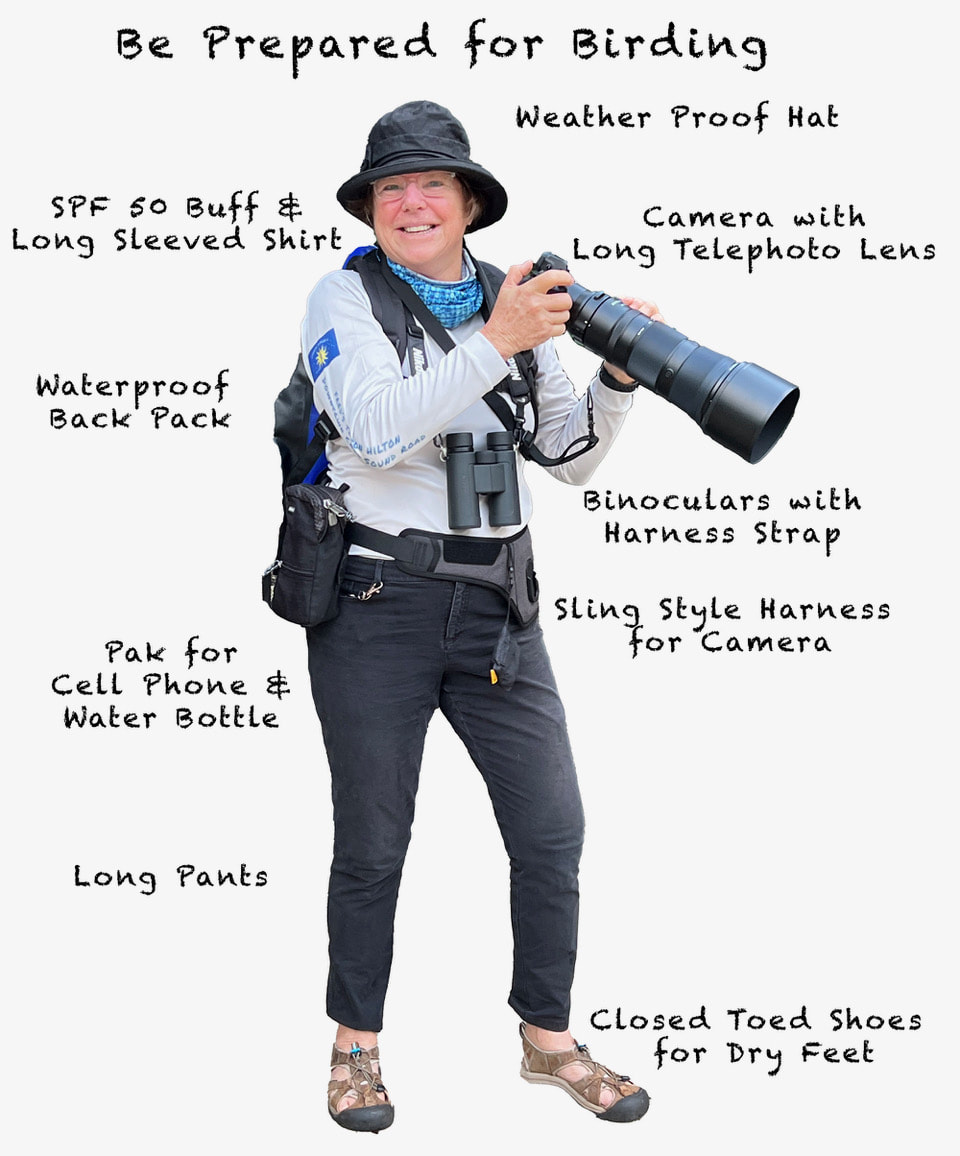

With its cooler, dryer temperatures, winter has finally arrived in the Florida Keys and the time to get out and explore nature is right here and now. With that in mind I signed up for the 2023 Croc Lake Audubon Christmas Bird Count. In its 5th year since becoming an official Count Circle, I was assigned to a group with an experienced birder and other volunteers to seek out and identify birds, keep the bird tally log, and photograph. The Christmas Bird Count is in its 124th year dating back to 1900, when ornithologist Frank Chapman started the tradition of the Christmas Bird Count (CBC) that would count birds during the holidays rather than hunt them. Prior to 1900, a "Christmas Side Hunt" tradition existed, where hunters at a Christmas gathering, would divide into teams, go out for an afternoon of killing wildlife, both furred and feathered, and return to tally up the dead carcasses and declare a winner. Can't really say anyone was the winner, as the animals were not even intended for the dining table. This was my second attempt at joining the CBC event. In 2022 I showed up ill prepared for the rainy weather, as we walked through wet grass, with now wet feet, plus my new camera anxiety caused me to quit after only an hour. The goal is to arrive at 7 am and count the entire day, and finish about 5 pm. So for 2023 I set out prepared. I had weather appropriate, lightweight clothing and closed toed shoes, a waterproof backpack to stash my camera gear in case of rain, sunscreen, water, and I had the most important item needed - an inexpensive pair of binoculars recommended by Audubon. In 2023 again we had rain, in fact four days of tropical squalls and daylong downpours preceded the count. The Sunday morning of the CBC, the weather was clearing, but rain arrived early. Our group decided to take a breakfast break until the rain cleared. Fellow volunteer and woodsman Jack rationalized, ”If the birds aren’t out in the rain, we probably shouldn’t be either.” An organized group event such as the CBC, held annually between December 14th and January 5th, is a great way to be outdoors and meet new people, and the count is free and open to everyone regardless of bird ID skill level. Don’t worry about what you don’t know, naturalists are very willing to share their knowledge with you. Birding is a challenge for sure. Especially if you are not familiar with their calls, have poor hearing or don’t know what you are looking at. I can check all of the above boxes! It was hilarious as the group would point out a bird that for the life of me I could not see. That’s normal, the bird has stopped moving, they assured me, look for the movement of the leaves. That helped, and when finally I saw the bird there would be a celebration. After finding the bird, raising the camera and getting in focus, I had to act quickly before the bird is gone. I guess that's why I have a lot of photos of birds flying away! The thrill of the hunt! The CBC is a great example of citizen science, the practice of enlisting a large group of volunteers to collect and share data as part of a larger story. Our group, one of six in this year’s Croc Lake CBC, sited 26 different species and 259 birds total that day. Aside from organized events such as the CBC, individuals can collect data on their own. Our group leader Chrissy told me she keeps track of the species of birds, and the dates they arrive to her yard. When I asked if she shared the info, she said it was more so she would know when to expect some of her favorite birds. My birder friend Harold encouraged me to enter data on eBird after my rare sighting of Black Swans in Key Largo this summer. He emphasized the importance of recording sightings, as trends show up over time, and are used to study the long-term health of bird populations. The only way the CBC could have been more fun is if there were more people doing it. By the end of the long day, we were power walking the trails so we could get to all the areas on our list. It would have been much better with more volunteers to divide the territory up into smaller portions and spend more time in observation. The weather’s great and the birds are here. Grab a friend and take a walk outside at Dagny Johnson Key Largo Hammock Botanical State Park, located on County Road 905, half-mile north of the intersection with U.S. Highway 1 at Mile Marker 106. It is open from sunrise to sunset 365 days a year.

0 Comments

My favorite times of day are near dusk and dawn. The time of day, when the shadows get longer and you can sit outside without a hat on, with coffee or cold drink in hand, and contemplate the wonders of nature. It’s the time of day full of chirping and songs, and the emergence of the critters. It’s the time before the sounds of daily human activities; the din of lawn mowers and leaf blowers, the constant chatter of workmen nearby. Think of how your morning walk would change if you pulled out the headphone plugs, and simply listened to the sounds of nature. Tune in not out. I will use my iPhone on nature walks; it has an app called “Merlin” that listens to and records bird sounds, and in real time suggests a possible identification. For me, a nature lover who basically knows nothing, it has opened up a world of knowledge, and has brought me even closer to nature. As the names of birds are popping up on the screen, you get an idea of what may be making the sound, and aiding you in visually identifying it. The app can also be used by someone with a hearing loss, someone who can hear, but the sounds may not be crisp enough. As areas are developed, and natural land is changed, birds lose their favorite trees and water sources. Several of my friends have installed screech owl nesting boxes, in their yards, within view of their windows or porches. In the wild, screech owls nest in abandoned holes created by woodpeckers for example. Before I get a nesting box, I need to use “Merlin” to see if I already have owls in my yard, or vicinity. There might just be a natural "house" in my wooded acreage. “Birders” are a pretty great bunch of people. A friend was invited for a cocktail at the home of a neighbor who had a “screech owl” nesting box in a palm tree outside the porch. Yes, lively Key Largo nightlife…sipping on a drink while listing to the “HOO”. She later found an appropriate spot in her own yard, where she could enjoy the owls, who came year after year thereafter, until hurricane Irma tore the house down. Have you ever heard someone say they never see any birds in their yards? Or maybe they do not know where to start looking for birds. The answer is, look in your backyard. Ask yourself, what does a migrating bird or even a local bird, have to eat in your yard? Do you have any native plants? With development and habitat loss, there are increasing pressures on wildlife. If everybody just planted one native plant, that's a start. In a suburban jungle one native tree may be fruiting, while in another there is pollen and nectar attracting bugs and caterpillars. That is what they need to eat. It's like you going to the store and there is only cat food there. What are you going to eat? Birds need fresh water, and cover too, so they may hide from predators. Owls can be a great source for natural pest control and it is free. No pesticide service or poison filled plastic boxes needed! Screech owls feed on all sorts of bugs, cockroaches, lizards, beetles, moths and rodents. Whatever they can see, catch in the air or pounce on is fair game. Spraying for bugs eliminates a food source. Owls can also be threatened by pest control of the another kind… rat traps containing poison are a huge problem. The rat entering the box does not just eat the poison and die there, they eat the poison, then leave the trap, to slowly die from the effects wherever they wander off to. Unfortunately for the birds of prey such as the owl, or the hawk, that same poison does not discriminate between the rat, and the bird that just ate the rat. For all of us, birds alert us to seasonal shifts like migration, teach us about communication, and the cycle of life through behaviors like predation, mating and nesting. Screech owls mate in late fall, and you can hear their noises. The baby owlets emerge from the nesting boxes in April or early May. Nature is the Law. It makes me want to get up early in the morning and keep going. The ecosystem is provided free of charge, no accessories required. And the benefits are lower rates of anxiety, depression and stress.

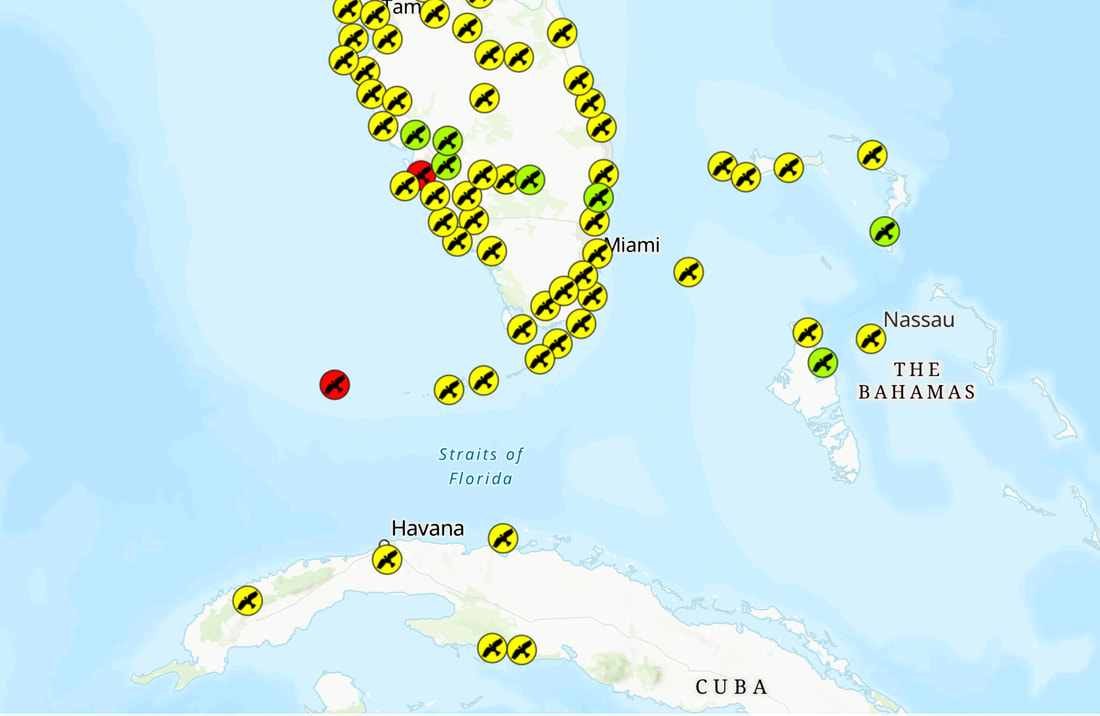

Bird photographers have the patience to sit behind a tree blind for hours waiting for the bird to appear. To the contrary, when I see a bird, I raise my camera to shoot and I get a photo of a bird flying away. One winter, when the birds are plentiful, I hired a guide to tour the Florida Keys Backcountry on his flats boat. The guide was skilled in finding birds, the only problem, the 500 horsepower announcement of our arrival, caused the birds to fly, which then resulted in a high speed pursuit from my perch in front of the center console, firing 10 continuous frames per second with my camera. A guide's reputation is only as good as the fish they catch, or in this case, birds that are sighted. We return to the dock with bird images captured, albeit flying away. Looking back at the experience, it is quite disturbing, for me to have disrupted the birds for the sake of a photo. The only consolation is, unlike James Audubon's artwork, I didn't have to kill the bird, in order to paint it. During July 2020, we're just emerging from Covid lockdown, and I get a call asking for help. My caller states he's undergoing cancer treatments and needs to focus on his camera to relieve some of his pain, and to feel productive. He wants to make a journal, and illustrate it with his photographs. At our first meeting, I thought I was there to solve some technical problem with the computer and the camera. By the third session with Joe the C.E.O. (I always promised to keep his identity confidential), I realized I was his teacher, and guiding light in this journey, which had no certain end. Joe was used to worldwide hunting excursions, and had impressive shots from those trips. But now with cancer, his travel was limited to what he could capture in his backyard. Fortunately for Joe, his backyard bordered on a wildlife refuge. where he was documenting the American Crocodile in the mangrove lined creek behind his house. Joe thinks the photos are not turning out so well. On first inspection, let's say his photos were extremely artsy. There was a little motion blur, camera blur, and a few photo filters added for good measure. Joe thought perhaps it's his camera. I viewed it as the challenges of low light photography, and just trying to make something good out of what he’s captured. I shared with him my recent experience involving my health, and how it affected my confidence and balance. I learned by attaching a mono-pod to my camera, my pictures would remain clear and in focus. I lent him my so called “photographer’s cane”, thinking perhaps his cancer treatments had affected his steadiness. Immediately his photos improved. He went on to photograph with extreme competency an amazing array of species from his lanai, including Bald Eagle, Osprey, Crocodile, Heron, Egret, Red Shouldered Hawk, Red Cardinal, and Iguana. The images were compiled into a coffee table book, prefaced with Joe’s words, and then he put the camera away. Yes, away. Project complete. On time and a little over budget. Fast forward to Spring 2021, not too far from Joe's lanai, in a small pool of water next to a bridge, I encountered a diverse group of wading birds, just hanging out. A rare sight, I had to give it a shot, so I set up my tripod and Hasselblad medium format camera. So far so good, it is quiet, the birds are unfazed by my presence behind the cover of a green buttonwood branch. The resulting sepia tinted photograph I call the "Breakfast Club” and features our winter wading and shoreline bird visitors including Roseate Spoonbill, Wood Stork, Little Blue Heron, Green Heron, Tricolored Heron, Snowy Egret, White Ibis, and Great White Heron. Seeing these birds congregating within a residential community was a special experience. In 2020, scientists captured ten adult Roseate Spoonbills nesting in Florida Bay and attached cellular tracking devices so they could learn about their nesting and foraging habits. They’ve found the birds are using more ponds inside bay keys than the mangrove wetlands on the mainland that they historically preferred. Audubon incorporates trail cameras to monitor nesting success. The photos taken by the cameras are able to capture truly candid images of every movement these birds make. I cannot wait to learn more and hopefully see more birds in the future.

Joe passed this year. I miss him, however his memory lives on, whenever I sight birds in our midst. |

CAROL ELLIS

This photographic website provides me the opportunity for self-expression, for sharing Archives

May 2024

TAGS

All

|

© Copyright 2022. Carol Ellis Photography.

All Rights Reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed