|

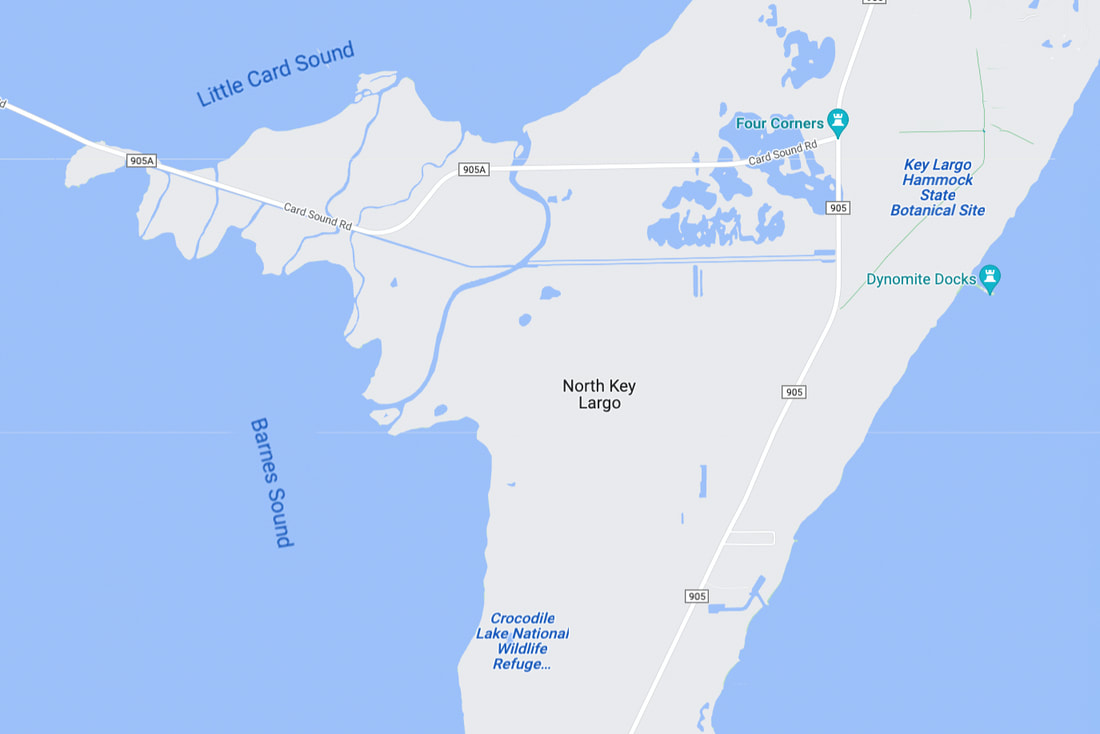

In 2020, my friend and naturalist Bunny Bradov spotted a rare butterfly in my garden. She dashed to her car to get her GPS and notepad. and I kept track of its movements. It was a Bahamian Swallowtail butterfly, attracted to the wild lime and wild coffee plants in my yard. A garden brings you closer to nature, as you breathe in fresh air and exhale that which no longer serves you. After my experience with Bunny, I found myself in the garden not only while contemplating my morning coffee, but also random times of day, checking on the birds, butterflies, and other critters residing or passing through. My definition of “weed” changed to “native nectar providing plant” for a White Peacock butterfly. After seeing the Bahamian Swallowtail, I signed up for the annual Schaus Swallowtail butterfly survey which takes place in the refuges of N. Key Largo each Spring and Summer. The Schaus Swallowtail (Papilio aristodemus ponceanus) is one of the rarest butterflies in the United States and has been listed as an endangered species by the State of Florida and the federal government since 1975. It once ranged from the Miami Hammocks to Lower Matecumbe Key, and there are some records that it had been seen on Key West. Today it is found only on northern Key Largo and several small Keys in Biscayne National Park. In 1984, numbers sank to an all-time low, when an estimated 70 or fewer adults were left in the wild. Studies showed that Monroe County Mosquito Control District spraying pesticides was the chief factor contributing to the rapid decline of the species. Jan 1991 Mosquito Control stopped spraying the hammocks of N. Key Largo. In 1991 and 1992 the populations rebounded. Unfortunately August 1992 Hurricane Andrew passed over the Upper Keys and Biscayne Bay and did great damage due to high winds and 4-10 ft storm surge covering Elliott Key for at least an hour. Luckily the National Park Service and the State had authorized the removal of 100 eggs from wild females on Elliott Key just 2 months prior, to start a captive breeding program at UF with the intention of reintroducing them into the wild. Each Spring, volunteers begin entering the hammocks to record sitings of the butterfly, and report back to researchers. If it is dry, chances are low for seeing a Schaus. Schaus’ pupa can remain inside their hard shelled cocoon for up to three years, until the environmental conditions are right, before emerging. North Key Largo generally receives more rainfall, than "downtown" Key Largo. Since I live in “uptown” northern Key Largo, close to the refuges and prime Schaus’ habitat, the group asked me to share daily rainfall totals, to better predict when the Schaus butterflies would emerge. Schaus are particularly dependent on precipitation. They lay their eggs on Torchwood (Amyris elemifera) and on Wild Lime (Zanthoxylum fagara). Abundant rainfall ensures there is enough new growth for the caterpillars to feed on. Butterfly surveyors get all “aflutter” when they think they’ve spotted their prize. This year, Bunny and I were surveying at Crocodile Lake NWR, when we spied a swallowtail on a native plant, but this time it is a Giant Swallowtail butterfly, a common species. Only Schaus and Bahamian Swallowtails are logged with GPS and time spotted, but all butterfly species are counted in the survey report. To survey in the summer heat with mosquitos, it takes some pretty hearty souls, with backgrounds as diverse as the plant community, yet all come with a passion and curiosity for nature. Linda Evans started butterflying in 2004 after one of her dental hygiene patients asked her to put signs in front of the butterfly plants at Fairchild Tropical Gardens, where she was driving the tram. She’s been involved ever since. “It’s a full-circle community conservation effort,” Crocodile Lake NWR refuge manager Jeremy Dixon said. “We have volunteers going out collecting seeds, growing the plants (Pennekamp nursery) and then planting them for the very butterflies they’re doing surveys for.” Planting native plants such as Torchwood and Wild Lime for the Schaus population is good management for the refuges, but it can also be a common sense approach for a home garden too, as we live in a world of dwindling natural spaces. The “right plant, in the right place” will thrive in your garden without costly chemicals or special maintenance. A garden is one of the few things in life you can control… somewhat… depending on the wind. In the last five years, a trend of concern involves companies promoting spraying services to create an "all kill" zone in people's yards. If you are trying to manage butterfly populations, and a butterfly cannot fly through someone's yard without getting killed, that’s a problem.

To learn more about our butterflies, or provide support, check out the Miami Blue Chapter of the NABA.

0 Comments

It was a beginning to a wonderful day, as I looked up and discovered a natural honeybee hive, nestled on a sturdy limb thirty feet up in a gumbo limbo tree. Hundreds of honeybees were thriving on the abundant resources of nectar, pollen, water and sunlight found in my Florida friendly yard. Upon sharing the news with my husband Ted, as he sat sipping his honey sweetened cappuccino, he urged me to get the bees out of the tree so they’ll be safe, as the limb supporting their growing nest may break. If you were the proverbial “fly” or “bee” on the wall, this is how the conversation went: Make the bees safe? How would that would work? He replied, "You put a box on the ground and the bees go in it." “Really… to get bees, you need a queen... where would you get the queen? "From the hive in the tree," he says. Silly me. I thought, how could it be that bees, who have survived in the wild for millions of years, all of a sudden need my assistance to live? I thought this was capitalizing on the bees rather than saving them, so I rejected that idea, and the bees continued to grow their hive. Then one clear September morning, I awoke to the sound of the mosquito control helicopter. Outside I found the honeybees were dying from the spray. I cried as I watched with awe as the bees were slowly dying due to the ignorance of people who should be preventing this type of carelessness. There must be a better way to control the mosquito population without indiscriminately blanketing everything with poison. That’s when I learned that the only way you can protect a hive is by covering it in advance of the spray with a wet sheet. The bees encounter the wet sheet, think it is raining, and stay inside. But since the hive was high up, the sheet method was not practical. I devised a plan for saving the bees by creating a little artificial rain shower over their hive by using my garden hose. The next spraying event we had better results. Rather than a hundred plus bees dying, the casualties were reduced to a couple dozen dead bees. Bees are important ... it goes without saying. Without bees there are no flowers to grace your dining table, no plants to eat. What is happening here? If I called a beekeeper to move the bees, who would pollinate the vegetables and flowers in my garden? Crazy mixed up world where you have some “men” protecting nature from the actions of other “men”. The bees do need our help to survive. Beekeepers, "keep" the bees for their honey, pollen and wax and in return, cover the beehives during spray events. Life is Tough. I found this out in 1988 when I spent a day with beekeepers Lois and Sid Tough who kept their hives behind the thick green walls of foliage lining old Card Sound Road in N. Key Largo. Tough kept his hives locally year round, at sites with names like “The Refrigerator” or “Broken Tree”, referring to landmarks in the area. He followed the blooms of the Keys mangroves, the Everglades palmetto, Florida holly and the Homestead farm crops and avocado groves. Tough moved his bees to different locations on Mondays, removed honey filled hives on Saturdays, and extracted the honey on Sundays, all while working five days a week at a Miami boat yard. Taking life in stride is part of “Tough’s Law”, which states that some days working is hard and other days it’s even harder. Tell that to the bees in my yard. Their hive rebounded after mosquito spraying, only to get whacked by hurricane Ian’s winds, which caused several “chambers” to fall to the ground. More bees died and the larvae contained within perished soon after. Somehow I had an easier time reconciling the loss of bees from this natural disaster, than to the pesticide spraying event weeks earlier. The Queen Lives!! At least in my bee hive in the Northernmost Territory of the Conch Republic. Thanks to Nelson Gordy whose passion for bees and the hobby of beekeeping is helping the likes of me and others who find themselves “keepers” of bees with great education and removal services.

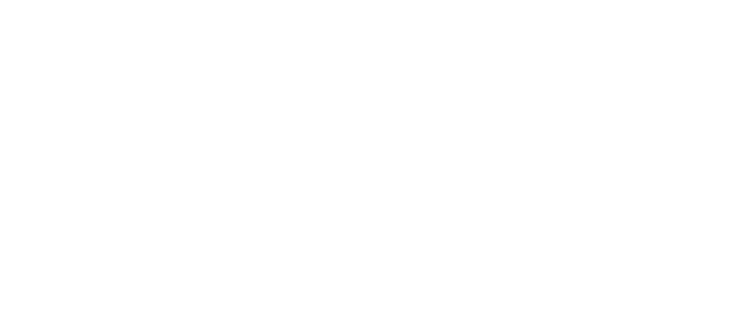

Though I probably will not become an official “beekeeper”, I do hope the queen and her hive remain happy and thriving in my Florida friendly yard. The Florida tree snail (Genus Liguus) range once extended from Pompano Beach to Key West and across the Everglades to Marco Island. It is hard to imagine a time when tropical forest trees were covered by their glistening shells. A tree snail was like an exquisite jewel.

Charles Torrey Simpson wrote, " Long before I began to collect (1882) man had wrought great destruction to the hammocks in which they live... they are on the verge of extinction. Great forrest areas have been cut.” Construction of the canals in Fort Lauderdale began in 1920 by clearing the mangroves and creating the first “finger islands” that became the trademark of Fort Lauderdale, “The Venice of America.” It was a model repeated by developers along the coasts, who were in the business of “selling mangroves” as they dredged and filled the wet lands and leveled the hardwood hammocks. On December 6th, 1947, the government set aside 1.5 million acres of protected land as Everglades National Park (ENP), one place where the bulldozers could not come. Federally designated threatened Stock Island tree snails were moved to N. Key Largo Hammocks as a part of mitigation for developers. Post WWII, a new generation of homeowners were on their way to South Florida. Common were sales pitches, like this one in 1952, describing the proposed development of Key Largo Beach: “Slumbering, awaiting the advent of fresh water and the mechanical work of modern machinery to restore this natural setting for the comfort and enjoyment of man today, this great flat rock key, high above the sea, on which great trees have survived for centuries, and thick with vegetation, lies basking in the sun with its frost free climate but tempered by the ocean breezes is this potential paradise.” Originally, every tree island, every plot of land had a different variety of liguus tree snail, with different bands and color variations based on their diet and conditions in their particular hammock. Conservationists were particularly worried about snails in the Keys, where U.S. 1 gave collectors easy access to the hammocks that were home to the snails. Collectors proposed that they transplant threatened snails to suitable hammocks in ENP. From the 1950's thru the mid 1960's, some 52 color varieties were relocated to 224 hammocks within the park.

“You build it and they will come,” an adage true, more now than ever before. Not long ago in Key Largo, there were still pockets of forest, and undeveloped waterfront; little by little all are being developed. There are regulatory things that have to be done when developers want to develop areas. Especially concerning the federally designated threatened Stock Island tree snails in the area. Mitigation goes on where park rangers have to go out and remove the snails, then the developers have to pay money and the question is what to do with the tree snails? They get put in suitable conservation lands in the refuges in N. Key Largo. This usually happened without a lot of people’s knowledge.

At the time, I did not understand the significance of what I was photographing. The accepted notion of moving and collecting has made science pause. Does conservation mean we must allocate a species to an area they were not native to, to forsake the environment of their origin? Our nature is a consequence of man’s actions. It would have been more interesting to know the Keys before people did what they did. Key Largo Beach city fathers predicted in 1969 the town would grow to 5000 by 1974

and 100,000 by 1990. Side-by side maps showing proposed development, and today’s current designation of the area as botanical and wildlife refuges. |

CAROL ELLIS

This photographic website provides me the opportunity for self-expression, for sharing Archives

February 2024

TAGS

All

|

© Copyright 2022. Carol Ellis Photography.

All Rights Reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed